The most popular book in history will soon be coming to your local plasma-screen television set. Mark Burnett, the producer of reality television series such as Survivor, The Apprentice, and The Contendor, is planning to produce a ten-part miniseries called The Bible for the U.S. cable television channel History. The series will inevitably prove groundbreaking, but one big question remains: does a collection of religious stories really belong on a television channel which purports to be devoted to history? As is often the case, there are two sides to the argument.

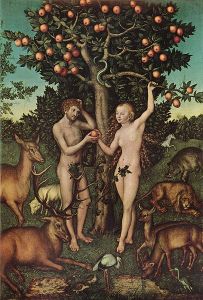

Production on the series is planned to take place throughout 2012, while the series itself is expected to air in 2013. According to Bill Carter of The New York Times, the series will not be presented as a documentary from a third-person perspective, but rather as a scripted dramatization from a first-person perspective. Each of the ten parts will be about two hours long, and each of these will feature two or three major stories from the holy book of the Judeo-Christian faith tradition. Likely candidates include stories from Genesis like the Creation and Noah's ark, Exodus, and the New Testament account of the life of Christ, but Burnett will also be working with lesser-known stories, Carter says.

Both Burnett and Nancy Dubuc, the president of History, have explained the inspiration behind the series.

Burnett suggested he was inspired by Cecil B. DeMille's classic film The Ten Commandments and said he wanted to bring the same majestic, epic style to the television screen. Epic-style production "used to be the purview of major motion pictures" but are now available for television, he said, adding that "[o]nce in a generation someone gets to breathe new visual life into that book". Essentially, for Burnett, the importance of the series lies in the powerful, moving cinematic effect created by portraying Bible stories onscreen.

This attention to the book's cultural currency is echoed by Dubuc, who has argued that the Bible is an historically significant collection of works. Carter quotes her as saying, "[t]his is the most discussed, debated book in the history of mankind", and that "[w]hat the book has come to represent, and the power of it and the importance of it is itself history". What Dubuc seems to be saying is that the Christian holy book, being "larger than life", has so influenced history that it has become the same thing as history itself. This does not make much sense, though. Something that affects history cannot be history itself. It is a paradox.

To solve this problem, let us make a distinction between history and Biblical tradition. We might argue that the Bible is a work of religious tradition, not a purely historical record of real events, and should therefore be treated as such.

To support this view, let us take a brief look at what history means. The word history can be defined as "the branch of knowledge dealing with past events", while historical can mean "having once existed or lived in the real world, as opposed to being part of legend or fiction or as distinguished from religious belief". According to Peter Seixas and David Lowenthal, the stories common to a particular culture, but not supported by external research (i.e. Arthurian legend), are often classified as cultural heritage, whereas history deals largely with detached, objective investigation 1, 2. In this sense, history connotes the discovery of what really happened in the past, not the celebration of religious beliefs and traditions.

Given this understanding of the meaning of history, Dubuc's view on the Bible seems questionable. She suggests that the book deserves its own series because it is "historically significant". But what does that mean? Does it mean that the Bible itself is historical, or that the Bible has influenced history? If it means the latter, the series should portray the book as an instrumental tool in shaping the course of history, not as a repository of history itself, since it consists largely of religious stories, not factual events corroborated by external sources. In other words, the series should not treat the Bible as a source of history, but as a part of history. Yet Dubuc seems to conflate history with legacy, creating the misleading impression that religious stories within history constitute history itself. Unwittingly, Dubuc herself suggests this: "We're not stepping back to examine anything that could be called a controversy. We are just telling the stories that are in it". But that is the whole point of a television channel that markets itself as a source of history to present religious literature within an historical framework, and not as the framework itself.

Additionally, History has been criticized for focusing on historical topics from a Western, especially American, worldview, which might explain why the channel is producing a series on religious beliefs cherished by Americans and Westerners. Maybe the people who run the channelare not trying to stimulate curiosity in its viewers about the outside world (or even produce high-quality educational content), but rather to re-affirm the traditions, beliefs, and biases already held by those viewers. Maybe it is this that lines their pockets.

Of course, we might be taking the format of History too seriously. After all, the channel does air non-historical reality programs such as Ice-Road Truckers, Ax Men, and Pawn Stars, so it is no surprise that it should also produce a dramatic series on religious stories and legends. That said, the Bible is arguably the keystone literary work in history, so it will be interesting to see how Burnett and his crew condense this collection of highly vivid religious allegory into an entertaining ten-part, twenty-hour visual experience. Such a feat has merit in its own right.

We always want to hear your side of the story. As a pastor or minister ordained online in a nondenominational church, do you like the way History plans to present the stories of the Bible?

Sources:

Seixas, Peter (2000). "Schweigen! die Kinder!". In Peter N. Stearns, Peters Seixas, Sam Wineburg (eds.). Knowing Teaching and Learning History, National and International Perspectives. New York & London: New York University Press. p. 24. ISBN 0-8147-8141-1.

Lowenthal, David (2000). "Dilemmas and Delights of Learning History". In Peter N. Stearns, Peters Seixas, Sam Wineburg (eds.). Knowing Teaching and Learning History, National and International Perspectives. New York & London: New York University Press. p. 63. ISBN 0-8147-8141-1.

0 comments